Is the Leonteif Utility Function Continuous

Introduction

Together with the Cobb–Douglas utility function, the Leontief utility function

$$\begin{aligned} u: \mathbb {R}^n_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R} \quad \text {with} \quad u(x) = \min \{a_1 x_1, \ldots , a_n x_n\} \qquad (n \in \mathbb {N}, a_1, \ldots , a_n > 0)\quad \quad \end{aligned}$$

(1)

is among the most commonly used in economics. It illustrates the case where commodities are perfect complements. Wassily Leontief, Laureate of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1973, introduced its functional form in the early 1930s for a production function rather than a utility function (Leontief 1941; Dorfman 2008). His idea was as follows. Suppose that producing an output requires fixed proportions of its \(n\) inputs. One unit of output requires a vector \((\alpha _1, \ldots , \alpha _n)\) of inputs, with all \(\alpha _i > 0\). Given input vector \(x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\), how much output can you produce? Well, looking at input \(i\), at most \(x_i/\alpha _i\) units. What constrains you are inputs \(i\) where this ratio is smallest: the maximal output is \(\min \{x_1/\alpha _1, \ldots , x_n/\alpha _n\}\) units, which is of the form (1) with \(a_i = 1/\alpha _i\). This functional form also provides the underpinnings of a number of theoretical constructs in the literature on technological efficiency, like Debreu's coefficient of resource utilization, the Solow residual, and total factor productivity (TFP); ten Raa (2008) gives a recent overview of these three concepts and their relations.

Instead of assuming that a utility function of a specific form exists, this note takes things one step back and derives Leontief utility functions from first principles: what properties of an economic agent's preferences \(\succsim \) assure that they can be represented by a Leontief utility function?

The crucial axiom is meet preservation (emphatically not 'meat' preservation, no matter what my apparently carni-industrially inclined spelling checker insists). It is a standard property borrowed from the literature on partially ordered sets and lattices (Birkhoff 1967; Davey and Priestley 1990); see Sect. 2 for details. The main results are:

- 1.

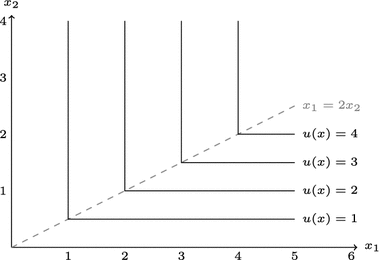

Theorem 3.1(a) shows that upper semicontinuity and meet preservation imply that upper contour sets have the familiar 'L-shaped' or 'kinked' form typical of Leontief-like preferences; see Fig. 1.

- 2.

Theorem 3.1(b) then characterizes preferences representable by Leontief utility functions, allowing some coordinates to be redundant.

- 3.

The axioms are shown to be logically independent in Sect. 4.

- 4.

As opposed to existing characterizations (Miyagishima 2010; Ninjbat 2012), Theorem 3.1 does not take the parameters \(a_i\) of the Leontief utility function (1) as given and use them explicitly in the axioms. Rather, the parameters are derived as consequences of the axioms; see the discussion in Sect. 5.

Related literature is discussed in the final Sect. 5, where I can more easily appeal to my earlier notation and axioms.

Indifference curves of utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^2_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) with \(u(x) = \min \{x_1, 2x_2\}\)

Preliminaries

Define preferences on a set \(X\) in terms of a binary relation \(\succsim \) ("weakly preferred to") which is:

complete: for all \(x,y \in X: x \succsim y, y \succsim x\), or both;

transitive: for all \(x,y,z \in X\), if \(x \succsim y\) and \(y \succsim z\), then \(x \succsim z\).

We call a complete, transitive relation \(\succsim \) a weak order. As usual, \(x \succ y\) means \(x \succsim y\), but not \(y \succsim x\), whereas \(x \sim y\) means that both \(x \succsim y\) and \(y \succsim x\). For \(x \in X\), denote the upper and lower contour sets by \(U(x) = \{z \in X: z \succsim x\}\) and \(L(x) = \{z \in X: z \precsim x\}\), respectively. Preferences \(\succsim \) are represented by utility function \(u:X \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) if

$$\begin{aligned} \forall x, y \in X: \qquad x \succsim y \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad u(x) \ge u(y). \end{aligned}$$

Let \(n \in \mathbb {N}\). The zero vector of \(\mathbb {R}^n\) is denoted by \(\mathbf {0}\). For vectors \(x,y \in \mathbb {R}^n\), write \(x \le y\) if \(x_i \le y_i\) for all \(i \in \{1, \ldots , n\}\) and \(x < y\) if \(x_i < y_i\) for all \(i \in \{1, \ldots , n\}\). Let \(\mathbb {R}^n_+ = \{x \in \mathbb {R}^n: x \ge \mathbf {0}\}\) and \(\mathbb {R}^n_{++} = \{x \in \mathbb {R}^n: x > \mathbf {0}\}\). Endow \(\mathbb {R}^n\) with its standard topology and subsets with the relative topology.

Let \(\succsim \) be a binary relation on \(X = \mathbb {R}^n_+\) and define:

upper semicontinuity: for each \(x \in X\), upper contour set \(U(x)\) is closed.

homotheticity: for all \(x, y \in X\) and all scalars \(t > 0\), if \(x \succsim y\), then \(tx \succsim ty\).

monotonicity: for all \(x,y \in X\), if \(x \le y\), then \(x \precsim y\).

nontriviality: there are \(x, y \in X\) with \(x \prec y\).

Most properties are standard. Nontriviality rules out that all alternatives are equivalent.

A partially ordered set \((X, \le )\) is a set \(X\) with a binary relation \(\le \) that is reflexive (\(\forall x \in X: x \le x\)), antisymmetric (\(\forall x, y \in X: x \le y, y \le x \Rightarrow x = y\)) and transitive (\(\forall x, y, z \in X: x \le y, y \le z \Rightarrow x \le z\)). For \(x, y \in X\), the interval \([x,y]\) is the possibly empty set \(\{z \in X: x \le z \le y\}\). A least (smallest) element of a subset \(Y\) of \(X\) is an element \(a \in Y\) with \(a \le y\) for all \(y \in Y\). If it exists, such a least element is unique: if \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) in \(Y\) are both least elements, then \(a_1 \le a_2\) and \(a_2 \le a_1\), so \(a_1 = a_2\) by antisymmetry. Likewise, a greatest (largest) element of \(Y\) is an element \(a \in Y\) with \(y \le a\) for all \(y \in Y\). An element \(x\in X\) is a lower bound of subset \(Y\) of \(X\) if \(x \le y\) for all \(y \in Y\) and an upper bound of \(Y\) if \(y \le x\) for all \(y \in Y\). A meet semilattice is a partially ordered set \((X, \le )\) containing the greatest lower bound or meet, denoted \(x \wedge y\), of each pair of elements \(x, y \in X\).

For our purposes, note that \((\mathbb {R}^n_+, \le )\) is a meet semilattice. The meet of vectors \(x, y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\) is

$$\begin{aligned} x \wedge y = (\min \{x_1, y_1\}, \ldots , \min \{x_n, y_n\}), \end{aligned}$$

the vector of coordinatewise minima: a lower bound \(z\) on \(\{x,y\}\) must satisfy, for each coordinate \(i\), \(z_i \le x_i\) and \(z_i \le y_i\), so \(z_i \le \min \{x_i, y_i\}\). So the greatest lower bound \(z\) has \(z_i = \min \{x_i, y_i\}\). Also, for every set \(X\), its collection of subsets \(2^X = \{Y: Y \subseteq X\}\) is partially ordered by set inclusion and is a meet semilattice. The meet of subsets \(Y\) and \(Z\) of \(X\) is \(Y \wedge Z = Y \cap Z\), and intersection of \(Y\) and \(Z\): a lower bound \(S\) of \(Y\) and \(Z\) must satisfy \(S \subseteq Y\) and \(S \subseteq Z\), so \(S \subseteq Y \cap Z\). So the greatest lower bound is \(S = Y \cap Z\).

Our final axiom, as announced in the introduction, is a classical property from the theory of ordered sets and lattices. This axiom was introduced in the literature on Leontief utility functions in a slightly different form, (2) below, by Ninjbat (2012):

meet preservation: For all \(x, y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\), \(x \wedge y\) is equivalent with the least preferred of \(x\) and \(y\):

$$\begin{aligned} {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} x \wedge y \precsim z &{} \text {for all } z \in \{x, y\}, \\ x \wedge y \succsim z &{} \text {for some } z \in \{x,y\}. \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$

Somewhat colloquially, in terms of preferences, the value of the meet \(x \wedge y\) of \(x\) and \(y\) is the meet of their values. The axiom compares three alternatives: \(x\), \(y\) and \(x \wedge y\), where an (unweighted) minimum is taken for each coordinate separately. But it is a stepping stone to a utility function (1) where, in contrast, the (weighted) minimum is taken over all coordinates of a vector.

Although we defined meet preservation for weak order \(\succsim \), it is usually defined (see Davey and Priestley 1990, p. 113) or (Birkhoff (1967), p. 24), who calls it 'meet morphism') in terms of functions between two (meet semi)lattices: if \((X_1, \le _1)\) and \((X_2, \le _2)\) are meet semilattices, a function \(f: X_1 \rightarrow X_2\) is meet preserving if for all \(x, y \in X_1\): \(f(x \wedge y) = f(x) \wedge f(y)\). It follows easily from the definitions that weak order \(\succsim \) on \(\mathbb {R}^n_+\) is meet preserving if and only if the lower contour mapping \(L: \mathbb {R}^n_+ \rightarrow 2^{\mathbb {R}^n_+}\) is meet preserving:

$$\begin{aligned} \forall x, y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: \quad L(x \wedge y) = L(x) \cap L(y). \end{aligned}$$

Likewise, \(\succsim \) is meet preserving if and only if the upper contour sets satisfy

$$\begin{aligned} \forall x, y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: \quad U(x \wedge y) = U(x) \cup U(y), \end{aligned}$$

(2)

Ninjbat (2012) calls (2) 'upper consistency'. I prefer the definition of meet preservation above: it highlights that it is nothing but a standard, common lattice theoretic property.

Representation theorem

The theorem below characterizes all preferences on \(\mathbb {R}^n_+\) that can be represented by a Leontief utility function. Part (a) singles out the difficult step of the proof: upper semicontinuity and meet preservation imply that upper contour sets have the familiar 'L-shaped' or 'kinked' form typical of Leontief-like preferences; see Fig. 1. Part (b) characterizes preferences representable by Leontief utility functions, allowing redundant coordinates.

Theorem 3.1

Let \(\succsim \) be a weak order on \(\mathbb {R}^n_+\).

- (a)

If \(\succsim \) satisfies upper semicontinuity and meet preservation, then

$$\begin{aligned} for~each~x \!\in \! \mathbb {R}^n_+~there~is~an~m(x)\! \in \! \mathbb {R}^n_+~ with: \quad \! U(x) \!=\! \{y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: y \!\ge \! m(x)\}.\!\!\nonumber \\ \end{aligned}$$

(3)

- (b)

\(\succsim \) satisfies upper semicontinuity, meet preservation, homotheticity and nontriviality if and only if there exist a nonempty subset \(I\) of the coordinates \(\{1, \ldots , n\}\) and scalars \(a_i > 0\) for all \(i \in I\) such that \(\succsim \) can be represented by the utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^n_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) with \(u(x) = \min \{a_i x_i: i \in I\}\).

Proof

(a): Let \(\succsim \) satisfy the two axioms. Then \(\succsim \) is monotonic: if \(x, y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\) have \(x \le y\), then \(x \wedge y = x\), so meet preservation gives \(x = x \wedge y \precsim y\). Hence, \(x \succsim \mathbf {0}\) for all \(x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\).

Let \(x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\). Define auxiliary set \(A = [\mathbf {0}, x] \cap U(x)\). Set \([\mathbf {0}, x] \subseteq \mathbb {R}^n_+\) is closed and bounded, and hence compact. The upper contour set \(U(x)\) is closed by upper semicontinuity. So their intersection \(A\) is compact and nonempty: \(x \in A\). Moreover, \(A\) is closed under (pairwise) meets: if \(a, b \in A\), then \(a \wedge b \in A\). That \(a \wedge b \in [\mathbf {0}, x]\) is evident. That \(a \wedge b \in U(x)\) follows from meet preservation: for some \(c \in \{a,b\}\), \(a \wedge b \sim c \succsim x\). (In lattice theory jargon, \(A\) is a sub-meet-semilattice of \(\mathbb {R}^n_+\).) But then compact set \(A\) has a smallest element: there is an \(m(x) \in A\) with \(a \ge m(x)\) for all \(a \in A\).

Why? Well, for each \(a \in A\), set \(S(a) = A \cap \{b \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: b \le a\}\) is a nonempty (\(a \in S(a)\)), closed (as the intersection of two closed sets) subset of compact set \(A\), and hence compact. \(A\) is closed under (pairwise) meets, so the sets \(\{S(a): a \in A\}\) have the finite intersection property. By compactness, their intersection \(\cap _{a \in A} S(a) = \{b \in A: b \le a \text { for all } a \in A\}\) is nonempty: there is a smallest element \(m(x) \in A\).

It remains to prove the equality \(U(x) = \{y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: y \ge m(x)\}\). Since \(m(x) \in A \subseteq U(x)\): \(m(x) \succsim x\). For each \(y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\) with \(y \ge m(x)\), monotonicity gives \(y \succsim m(x)\). By transitivity of \(\succsim \): \(y \succsim x\). This proves that \(U(x) \supseteq \{y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: y \ge m(x)\}\). Conversely, let \(y \in U(x)\). Also \(m(x) \in U(x)\), so \(y \wedge m(x) \in U(x)\) by meet preservation. Moreover, \(\mathbf {0} \le y \wedge m(x) \le m(x) \le x\), so \(y \wedge m(x) \in [\mathbf {0}, x]\). Together, it follows that \(y \wedge m(x) \in A\). As \(m(x)\) was the smallest element of \(A\): \(y \wedge m(x) \ge m(x)\), i.e., \(y \ge m(x)\). This proves that \(U(x) \subseteq \{y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+: y \ge m(x)\}\).

(b): First, let \(\succsim \) be represented by a Leontief utility function of the form \(u(x) = \min \{a_i x_i: i \in I\}\) as in (b). Since \(u\) is continuous, homogeneous and nonconstant, \(\succsim \) is (upper semi)continuous, homothetic and nontrivial, respectively. For meet preservation, let \(x, y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\). By monotonicity of \(u\): \(u(x \wedge y) \le u(x)\) and \(u(x \wedge y) \le u(y)\), so that \(x \wedge y \precsim x\) and \(x \wedge y \precsim y\). It remains to show that \(x \wedge y \succsim x\) or \(x \wedge y \succsim y\), i.e., \(u(x \wedge y) \ge \min \{u(x), u(y)\}\). For each \(j \in I\): \(a_j x_j \ge \min \{a_i x_i: i \in I\} = u(x) \ge \min \{u(x), u(y)\}\) and, likewise, \(a_j y_j \ge \min \{u(x), u(y)\}\). Hence, for each \(j \in I\): \(a_j (x \wedge y)_j = a_j \min \{x_j, y_j\} = \min \{a_j x_j, a_j y_j\} \ge \min \{u(x), u(y)\}\). Hence, \(u(x \wedge y) = \min \{a_i (x \wedge y)_i: i \in I\} \ge \min \{u(x), u(y)\}\).

For the opposite direction, let weak order \(\succsim \) satisfy the axioms. Function \(m: \mathbb {R}^n_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^n_+\) defined in (3) is homogeneous. Indeed,

$$\begin{aligned} \forall x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+, \forall t \in [0, \infty ): \qquad m(tx) = t m(x). \end{aligned}$$

(4)

To see this, let \(x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\). By monotonicity, \(U(\mathbf {0}) = \mathbb {R}^n_+\), so \(m(\mathbf {0}) = \mathbf {0}\). This proves (4) if \(t = 0\): both sides of the equation equal \(\mathbf {0}\). Next, let \(t > 0\) and let \(y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\). Then

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{lllllll} y &{} \succsim x &{}&{} \Leftrightarrow &{} ty &{} \succsim tx \quad \quad \quad \quad \hbox {(by homotheticity, twice, once for each direction)} \\ &{}&{}&{}\Leftrightarrow &{} ty &{} \ge m(tx) \quad \quad \quad \qquad \qquad \qquad \hbox {(by (3))} \\ &{}&{}&{} \Leftrightarrow &{} y &{}\ge \frac{1}{t} m(tx) \quad \quad \quad (\hbox {by division by } t\, > \,0). \end{array} \end{aligned}$$

By (3), \(y \succsim x\) if and only if \(y \ge m(x)\). By the previous line, \(y \succsim x\) if and only if \(y \ge \tfrac{1}{t} m(tx)\). Therefore, \(m(x) = \tfrac{1}{t} m(tx)\), i.e., \(t m(x) = m(tx)\).

Since \(\succsim \) is upper semicontinuous and homothetic on \(\mathbb {R}^n_+\) and \(x \succsim \mathbf {0}\) for all \(x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\) [see (a)], it can be represented by a utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^n_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) that is upper semicontinuous and homogeneous of degree one (Dow and Werlang 1992, Theorem 1.7, p. 391). Since \(u(\mathbf {0}) = u(2 \cdot \mathbf {0}) = 2 u(\mathbf {0})\), we see that \(u(\mathbf {0}) = 0\). By monotonicity and nontriviality, there is an \(x \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\) with \(u(x) > u(\mathbf {0}) = 0\). By monotonicity and homogeneity, \(u\) has range \([0, \infty )\). In particular, \(u(y) = 1\) for some \(y \in \mathbb {R}^n_+\). As \(y \succ \mathbf {0}\), \(m(y) \ne m(\mathbf {0}) = \mathbf {0}\): nonnegative vector \(m(y)\) has at least one nonzero coordinate. Let \(I = \{i \in \{1, \ldots , n\}: m(y)_i > 0\}\) and \(a_i = 1/m(y)_i > 0\) for all \(i \in I\). I show that \(u(x) = \min \{a_i x_i: i \in I\}\), making \(u\) of the desired Leontief form. Let \(r \in [0, \infty )\). Using homogeneity of \(u\) and \(m\):

For the third equivalence, note that \(x_i \ge r m(y)_i\) automatically holds if \(m(y)_i = 0\). As \(u(x) \ge r\) if and only if \(\min \{a_i x_i: i \in I\} \ge r\), it follows that \(u(x) = \min \{a_i x_i: i \in I\}\). \(\square \)

Logical independence

The axioms in Theorem 3.1 are logically independent. We show this with four preference relations, each violating exactly one axiom in Theorem 3.1(b). Verifying that these preferences satisfy the given properties proceeds along the same lines as the proof of Theorem 3.1, so in the interest of brevity, we only show explicitly which axiom is violated.

Weak order \(\succsim \) on \(\mathbb {R}^2_+\) represented by utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^2_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) with \(u(x_1,x_2) = x_1 x_2\) satisfies all properties in Theorem 3.1(b), except meet preservation: if \(x = (1,2)\) and \(y = (2,1)\), then \(x \wedge y = (1,1)\) is strictly worse than both \(x\) and \(y\).

Weak order \(\succsim \) on \(\mathbb {R}^2_+\) represented by utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^2_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) with \(u(x_1,x_2) = 1\) if \(x > \mathbf {0}\) and 0 otherwise satisfies all properties in Theorem 3.1(b), except upper semicontinuity: the upper contour set \(U(1,1) = \mathbb {R}^2_{++}\) is not closed.

Weak order \(\succsim \) on \(\mathbb {R}^2_+\) represented by utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^2_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) with \(u(x_1,x_2) = \min \{x_1^2, x_2\}\) satisfies all properties in Theorem 3.1(b), except homotheticity: if \(x = (1,1), y = (1/2,2)\), and \(t = 16\), then \(u(x) = 1 > 1/4 = u(y)\), so \(x \succ y\), but \(u(tx) = 16 < 32 = u(ty)\), so \(tx \prec ty\).

Weak order \(\succsim \) on \(\mathbb {R}^2_+\) represented by a constant utility function satisfies all properties in Theorem 3.1(b), except nontriviality.

Related literature

In Theorem 3.1, an extra indispensability axiom, requiring positive amounts of all goods for improvements upon the zero vector, characterizes preferences representable by a Leontief utility function where all parameters are positive. The axioms remain logically independent. See the slightly more extensive working paper version (Voorneveld 2014).

The axiomatic literature on preferences and utility/production functions of Leontief form is surprisingly small. In terms of production functions, the motivation in the introduction by production processes with fixed proportions of inputs usually suffices. Then there is a tangentially related literature on functional equations that presumes the existence of a function, imposes some properties the function must satisfy and derives that it must be of the Leontief form. A recent example in a game theoretic model where payoff functions are Leontief-like is (Horvath 2012). Our approach is more difficult: rather than assuming that a function with desirable properties exists, we need to derive its existence and properties from assumptions on an agent's preferences.

There is substantial literature characterizing orders that can be represented by a Leontief utility function \(u: \mathbb {R}^n_+ \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) of the form \(u(x) = \min \{x_1, \ldots , x_n\}\) with equal weights on the coordinates. This is the maximin ordering that is of central importance in a variety of branches in the social sciences; (Mosquera et al. (2008), p. 144) give a nice overview. This literature started off with Milnor (1954). Later important contributions include Hammond (1976), Barberà and Jackson (1988), and Segal and Sobel (2002). These papers, however, do not consider the case with different parameters \(a_i\) for the coordinates. Moreover, they do not use lattice-theoretic axioms other than standard monotonicity requirements.

The two papers I am aware of that do consider Leontief utility functions with different weights are Miyagishima (2010) and Ninjbat (2012). The latter, as mentioned in Sect. 2, uses an 'upper consistency' axiom that is equivalent with meet preservation. These authors, however, answer a different question. They take the parameters \(a = (a_1, \ldots , a_n)\) of the Leontief utility function as given. Then they formulate axioms where these weights play an essential role [\(a\)-Hammond consistency in (Miyagishima (2010), p. 2); axiom A.2', symmetry with respect to the line through the origin and \((1/a_1, \ldots , 1/a_n)\) in (Ninjbat (2012), p. 21)], and characterize preferences that can be represented by the particular Leontief utility function with \(u(x) = \min \{a_1 x_1, \ldots , a_n x_n\}\). I rather wanted the parameters of the utility function to be endogenous, to follow logically from the axioms, instead of assuming what they are from the outset and using them explicitly in the axioms. In other words, Miyagishima (2010) and Ninjbat (2012) answer the question 'Which preferences can be represented by a particular, given Leontief utility function?', whereas I answer the question 'Which preferences can be represented by a Leontief utility function?'.

References

-

Barberà, S., Jackson, M.: Maximin, leximin, and the protective criterion: characterizations and comparisons. J. Econ. Theory 46, 34–44 (1988)

-

Birkhoff, G.: Lattice Theory. Volume 25 of Colloquium Publications. American Mathematical Society, Providence. 3rd edition (1967)

-

Davey, B.A., Priestley, H.A.: Introduction to lattices and order. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1990)

-

Dorfman, R.: Leontief, Wassily (1906–1999). In: Durlauf, S.N., Blume, L.E. (Eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2nd edition (2008)

-

Dow, J., Werlang, S.R.d.C.: Homothetic preferences. J. Math. Econ. 21, 389–394 (1992)

-

Hammond, P.J.: Equity, Arrow's conditions, and Rawls' difference principle. Econometrica 44, 793–804 (1976)

-

Horvath, C.: Nash equilibria on topological semilattices. J. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 11, 315–332 (2012)

-

Leontief, W.: The Structure of American Economy, 1919–1929. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (1941)

-

Milnor, J.: Games against nature. In: Thrall, R., Coombs, C., Davis, R. (Eds.) Decision processes. Chapman & Hall, pp. 49–59 (1954)

-

Miyagishima, K.: A characterization of the maximin social ordering. Econ. Bull. 30, 1278–1282 (2010)

-

Mosquera, M., Borm, P., Fiestras-Janeiro, M., García-Jurado, I., Voorneveld, M.: Characterizing cautious choice. Math. Soc. Sci. 55, 143–155 (2008)

-

Ninjbat, U.: An axiomatization of the Leontief preferences. Finn. Econ. Papers 25, 20–27 (2012)

-

ten Raa, T.: Debreu's coefficient of resource utilization, the Solow residual, and TFP: the connection by Leontief preferences. J. Prod. Anal. 30, 191–199 (2008)

-

Segal, U., Sobel, J.: Min, max, and sum. J. Econ. Theory 106, 126–150 (2002)

-

Voorneveld, M.: From preferences to Lontief utility. Working paper at Social Science Research Network (2014)

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40505-014-0034-8

0 Response to "Is the Leonteif Utility Function Continuous"

Post a Comment